This is an article from Aftenposten Innsikt translated into English. Les artikkelen på norsk her.

Oceans of Opportunities?

Norway is the world’s largest producer of Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout. Fish farming is the country’s second largest export, salmon exports alone totalling 106bn Norwegian kroner in 2022. And there is more to come.

The Norwegian Government’s strategy for aquaculture at sea is one for continued expansion. At the same time, there is vociferous criticism of the industry’s emissions and problems with fish health and animal welfare. But despite these problems receiving more attention, the Norwegian Veterinary Institute’s latest report on fish health, from 2022, shows that the challenges are real – and mounting.

«The report showed higher mortality than ever before, and health and welfare challenges more severe than ever», says Trygve Poppe, professor emeritus of fish health at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. He is one of the country’s foremost experts on fish health and has studied diseases in fish since 1981.

«The report has been published annually for 20 years, so changes in the health of Norwegian farmed fish are well documented. Fish farming is a billion NOK industry, with all the innovation and modern technology one might wish. So why on earth does it not improve, and why do we not see results in the form of lower mortality and better welfare?»

Nevertheless, Poppe thinks the increased public focus on both fish health and welfare is a good thing.

«In the 1980s, we barely gave welfare a thought, so in that sense things have improved. But even if work is being done to improve conditions, the way fish is farmed aggravates the situation. That is quite paradoxical.»

He reminds us that this is happening despite the new Animal Welfare Act having come into force in 2010. «As a starting point, it is a very good act. But even though it is meant to give fish the same protection as other farm animals, fish welfare has only got worse.»

Poppe finds there are many reasons for this.

«It has to do with, amongst other things, the structure of the industry, the wish for growth and higher efficiency. But this is biological production, not the manufacturing of screws and nails», he says.

Fish Experience Pain

Poppe’s view is that our ethical mindset when it comes to fish is different from that for other animals.

«Cows and pigs are animals, whilst fish are fish. Fish do not trigger the same emotions in us as a puppy or a lamb. Fish cannot communicate with us, and they live in an environment which is alien to us. But it has been proved beyond doubt that fish experience positive and negative emotions like other farm animals, and so should in principle be treated equally well.»

Analysis of the salmon’s ability to feel pain, of its memory, social intelligence, and ability to learn, indicate that they, like other animals, should be allowed to live out their biological functions and benefit from the same moral considerations as other animals. In an article, the Veterinary Institute puts it like this: “It is important to reflect on animal welfare as being a matter of the individual animal’s perceived quality of life.»

And, according to the Norwegian Animal Welfare Act, the fish is an individual. Trygve Poppe thinks this is also a matter of how we talk about fish.

«As a fishing nation, Norway has never looked at cod or mackerel as individual fish. They are measured in tonnes. The fish farming industry has taken this one step further when it talks about biomass and wastage, rather than individuals and death.»

And the number of deaths was record high in 2022: 92.3 million salmon and 5.6 million rainbow trout, if you count all fish that have died during the juvenile freshwater stage and the ongrowing stage in sea water. 2022 saw 56.7 million dead salmon in the seawater stage alone, an increase of 2.7 million from 2021. This means that the average mortality for salmon in the seawater stage in 2022 was 16.1 percent.

In its summing up, the Veterinary Institute points to «a number of diseases linked to intensive production and the handling of fish during delousing. Ulcers, gill problems and bacterial diseases contributed to the increased mortality rate». The Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR) concurs: «Amongst the most significant causes are delousing treatments, diseases and water quality.»

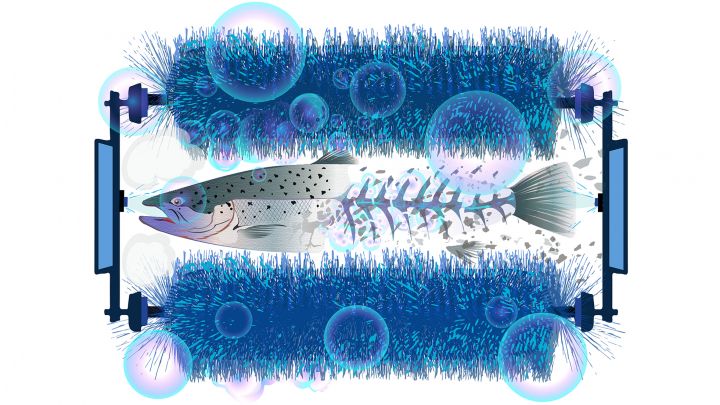

Harmful Brushing Non-medicinal treatment which requires handling of the fish, has proved to be a major welfare challenge. If the salmon is already sick or weakened from infections, it does not tolerate handling well. There are three main non-medicinal treatments for salmon lice: thermal (warm water), mechanical (water-based flushing and brushing) and the use of fresh water. These treatments are also used in combination. When the fish farmers must resort to such rough methods, it is because their «toolbox of less invasive methods is empty», according to the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. Illustration: Efi Chalikopoulou

A Financial and Ethical Problem

«From a financial and sustainability perspective, the loss of almost 60 million salmon is an enormous food waste problem, and also a waste of salmon feed, electricity and other production inputs. In addition, there is the aspect of animal ethics and moral. The mortality is an indication that the production makes the fish sick, and that animal welfare is too low in marine aquaculture. This is in marked contrast to animal health and welfare in agriculture, which we by rights can be proud of», says Trygve Poppe.

Kristine Gismervik, is scientific coordinator for fish welfare at the Veterinary Institute, and one of the authors of the Norwegian Fish Health Report 2022. She too sees mortality as an important indicator of health and welfare.

«Mortality does not tell us a lot about high levels of welfare, but it is a rough and much used indicator of low welfare levels, particularly when the mortality rate is high. In most cases, the dead fish has had a low level of welfare until it died.»

Gismersvik finds this trend worrying. Like Trygve Poppe, she does not see a great deal of improvement, despite there being ever more knowledge.

She also thinks that since no one wishes to produce with high mortality or low welfare levels, the authorities, fish health personnel [veterinarians and aqua medicine biologists] and the industry will all want to pull in the same direction.

The Louse Problem

Gismervik is clear that salmon louse treatment is the main threat to fish health.

The salmon louse is an ectoparasite which adheres to the salmon’s skin and feeds on its skin, mucus and blood. This leads to ulcers, which expose the fish to secondary infections. Open pens with a high concentration of fish give optimal conditions for the louse which, alongside escaped farmed fish, is the biggest threat to wild salmon, a species added to Norway’s list of threatened species in 2021.

The Norwegian fish farming industry spends billions of NOK every year on so-called delous-ing. For a long time, chemical treatment (with the controversial substance hydrogen peroxide) and medicinal treatment (both in the water and by mixing insecticides in the feed) have been the most common methods.

However, questions have been raised over the toxic effects these substances have on the environment. And, as the louse becomes increasingly resistant to medicinal treatment, the industry has increasingly moved to what is known as mechanical or non-medicinal delousing and water bath treatments.

But the handling of the fish during non-medicinal treatment increases the risk of a drop in oxygen saturation, stress, scale damage and death. The methods used include flushing and flushing combined with brushing, use of fresh water, and thermal delousing with warm water.

In the midst of these new methods the wellboats and the delousing vessels have taken a dominant position. A new lucrative industry has been created on the back of fish farming’s enormous welfare problems.

«With all these methods, the fish are first crowded together to obtain high density, before they are pumped into the units for treatment. After the delousing, the fish is pumped back into the pens. This gives rise to both stress and injuries, and also increases the risk of disease transmission», says Gismervik.

She explains that thermal delousing by using warm water (at 28-34C), which has become the most used method in the industry, exposes the cold-blooded fish [who’s body temperature is mainly regulated by its environment] to severe pain, also brought on by crowding and pumping.

The crowding process and the actual treatment with warm water can cause the fish to panic, which may result in injuries, spine fracture and increased mortality. This insight has been gained from the annual survey carried out in connection with the Fish Health Report, as well as through research into pain behaviour in salmon in 2018, carried out by the Veterinary Institute and the Institute of Marine Research, commissioned by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority.

Flushing, where water jets are used to remove the louse, is another much used delousing method.

«If the louse proves difficult to remove, the fish scales will be flushed off at the same time. These can grow back, but we see that bigger scale losses at winter temperatures can give rise to different types of bacterial winter ulcers.»

Another method involves placing the fish in fresh water.

«In nature, an anadromous fish like salmon will spend part of its life cycle in both fresh water and sea water. But a forced freshwater treatment makes for a very sudden change, and the treatment period can be extensive», says Gismervik.

Laboratory trials have shown that salmon lice can survive on the host for as long as 14 days in fresh water. Furthermore, a risk analysis carried out by the Food Safety Authority shows that the salmon louse can increase its tolerance after repeated exposure to fresh water.

Infections Increase Delousing Risks

The non-medicinal delousing methods also need to be seen in the context of the fish’ general health, which affects how well the fish can tolerate the treatment, according to Gismervik.

She describes the consequences of the rough treatments as a vicious circle.

Water circulates through the open pens, which not only expose the fish to lice, but also to other diseases, viruses, bacteria, and algae. The spread of diseases between fish also increases with fish density. Adding to this, a stressed fish can have a weakened immune system, and ulcers and tears from the delousing are susceptible to infections. Diseases and infections that follow, can in turn make the fish less able to tolerate the next delousing treatment.

Professor Poppe agrees with Gismervik, that the underlying general health of the fish determines how well it tolerates delousing. He lists several diseases farmed fish can be exposed to in open pens, amongst others viral diseases like cardiomyopathy syndrome (CMS), also known as Broken Heart Disease, inflammation of the heart muscle and skeletal musculature, Pancreas Disease (PD), and Infectious Salmon Anaemia (ISA). Various gill diseases can also weaken the fish. Of these, only PD and ISA are notifiable diseases, which Poppe fears may also lead to outbreaks of other diseases going unreported.

Poppe is particularly concerned about the heart problems linked to the intensification of the smoltification phase.

«The current production of smolt (salmon in the first (freshwater) part of its life cycle) is intensive and highly efficient, ensuring that the fish grows faster in order to reduce the time it spends in the sea, where they are exposed to diseases and salmon lice. But it has been proved that this can lead to deformations and small hearts, with resulting impairments. This will, in turn, increase the risk of mortality from the stresses of delousing», he says.

The Veterinary Institute’s report states that not enough is known about how the number of delousing treatments, handling generally, and the interval between treatments affect the farmed fish. This, despite several hundred million NOK having been spent on louse research, making the salmon louse one of the best researched species in the Norwegian nature.

«The variations and combinations of non-medicinal treatments complicate the statistics, and the only thing which is reported is that delousing has taken place, along with a free text field used to varying degrees. More accurate data is needed to better assess which treatments cause what», says Gismervik at the Veterinary Institute.

According to the industry’s self-reporting of «welfare incidents» (18781 reports in 2022), 42 percent were linked to non-medicinal delousing which required handling. Even if this is 61 percent lower than the self-reported incidents for 2019, the Institute’s survey of fish health personnel and inspectors from the Food Safety Authority showed that «Mechanical injury related to delousing» was rated as the most important reason for reduced welfare at both seawater production sites and broodstock sites with salmon and rainbow trout. The non-medicinal methods were meant to make headway in the fight against the louse. Instead, fish welfare decreased.

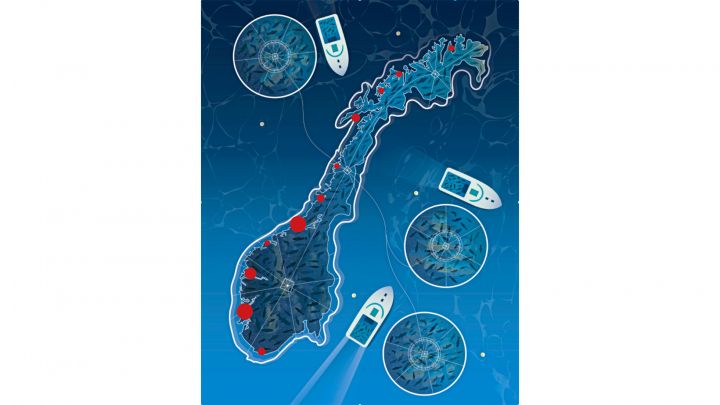

Heartache The number of non-medicinal treatments for salmon louse of farmed fish has increased substantially in recent years. They all involve some form of crowding, pumping, sorting and other rough treatment, which are all stressful for the fish, and which appears to be a significant factor in outbreaks of disease. One is CMS, so called Broken Heart Disease, a viral disease which can cause massive inflammation of the fish’s heart, weakening the atrium. In its report, the Veterinary Institute asks if it is justifiable, from an animal welfare point of view, to subject fish which are already unwell to repeated treatments. The red dots, size relative to impact, show the number of locations in each production area with outbreaks of Broken Heart Disease in 2022. Illustrations for Aftenposten Innsikt: Efi Chalikopoulou

Effect of Cleanerfish Questionable

Another non-medicinal «treatment», is the use of large numbers of cleanerfish, caught in the wild or farmed. These have their own welfare problems and have been named fish farming’s green martyrs.

Cleanerfish is a common name for lumpfish and various wrasse species, which are released into the pens, where the idea is that they eat the lice off the salmon. The effect of this method, according to the lates fish health report, has been questionable. Nevertheless, in 2022 the Norwegian fish farms released 30.3 million cleanerfish into the pens, according to biomass data from the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries. Nearly 60 percent of these are registered to have died, and the fate of the others is unknown.

The natural habitat of cleanerfish is markedly different from the environment of the salmon pens, which are often placed in sites with strong currents. Cleanerfish handle the delousing treatments badly and it is difficult to fish them out prior to delousing.

Professor Poppe characterize the use of cleanerfish as «insane»: «Not all cleanerfish specialise in eating lice. Many just eat the fodder given to the salmon. We watch this with our eyes wide open, well aware of the fact that most of them will just die.»

Painted into a Corner

Simple solutions to the current problems are few.

Unless mortality is reduced and welfare improved, Gismervik at the Veterinary Institute finds the Norwegian authorities’ wish for growth in this industry completely unacceptable. Seeing the need for gaining control, she believes the problems has to be solved on a political level, led by the Ministry and the Food Safety Authority.

– It is crucial that the Animal Welfare Act is used actively to improve welfare, and the new White Paper about animal welfare to be presented in 2024, will hopefully tell us how, she says.

A Cry for Help The Veterinary Institute’s Fish Health Report for 2022 shows that mortality in the sea phase in Norwegian fish farming in 2022 was 16.2 percent for salmon and 17.1 percent for rainbow trout, both higher than the previous years. There are significant differences in mortality between regions and sites. An area between Karmøy and Sotra on the south-west coast of Norway, had the highest mortality (23. percent), while the lowest mortality (9.1 percent) was found between Kvaløya and Loppa in Finnmark, Norway’s most northerly region. Illustrations for Aftenposten Innsikt: Efi Chalikopoulou

Defined by Human Needs

Researcher Annichen Kongsvik Sæteren at the Scandinavian Institute of Maritime Law at the University of Oslo is writing her PhD on the developments of animal welfare law and the regulation of salmon farming. According to her, the Animal Welfare Act should, in principle, pave the way for good protection of farmed fish.

«The act protects all animals equally, which means that farmed fish have the same protection as pets, and farm animals.»

The purpose of animal protection law is to set out the boundaries of what humans can do to and with animals, and also regulate humans’ duties to the animals, she explains.

«The consideration is the need of the humans, and whether they justify letting the animal suffer. Even so, the law gives absolute limits; some things are so harmful to animals that they are illegal even when there are strong human needs.»

She points to delousing and the use of cleanerfish, which is currently permitted by Norwegian authorities.

«The big question is whether the Food Safety Authority is complying with the Animal Welfare Act in accepting this. There is a basis in the Act for saying that these practices may be illegal», says Kongsvik Sæteren.

«One example is that the Act stipulates that fish are to be kept in an environment where they can live a good life, and that they are to be protected against injury. But fish kept in open pens will routinely be exposed to injuries through delousing, because they are exposed to lice.»

She adds that the same provisions apply when it comes to cleanerfish.

«It is more difficult to argue that the use of cleanerfish is legal than illegal, given that most of them die in the pens.»

«More specific guidance from the authorities is needed, in this case the Government, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries and the Food Safety Authority. Such guidance should make it clear if or when mechanical or thermal treatment is illegal and if or when it is illegal to keep cleanerfish.»

«The Food Safety Authority cannot use unclear guidelines as an excuse for failing to address this, as they are able to draft the guidelines themselves», Kongsvik Sæteren says.

She has yet to see that a regulation motivated by animal welfare, for the best of the fish and disadvantage for the industry.

«Since the Animal Welfare Act came into force, a lot of knowledge has been gained about how fish in farms can be injured and stressed, but the authorities do not apply this knowledge to communicate where the lines should be drawn. This is worthy of criticism», says the lawyer.

Wishes to Reduce the Number of Delousing Treatments

In an email to Aftenposten Innsikt, the head of regulation and control at the Food Safety Authoriy, Inge Erlend Næsset, writes that his organisation is in a difficult dilemma and has to make hard decisions about how best to use their available resources. The organisation is tasked with both inspections and the proposing of regulations for new and higher standards of animal welfare. Of 1000 pre-announced inspections in 2022, one or more breaches of fish health and welfare were found in 65 percent of the cases.

«The Food Safety Authority finds that too many farmed fish lack the welfare levels laid down in the Animal Welfare Act, and that too many fish are exposed to diseases and repeated, stressful treatments for salmon lice, which again contributes to the high mortality», writes Næsset. The Authority has, amongst other things, suggested a limit on how many non-medicinal delousing treatments a site can carry out, and still be able to obtain an exemption from the size restrictions placed on production sites in a red* areas.

(* There is a traffic light system where the environmental impact of the salmon louse in a specific production area gives a green, amber or red light. Sites in a green light area may be allowed to increase their production by 6 percent, amber sites are not allowed any increase and sites in red areas can be required to reduce production by 6 percent.)

The Food Safety Authority is also working on formulating the proposals for measures, to be set out in the new White Paper on animal welfare, expected in 2024. According to the Authority, they have previously highlighted a number of issues in need of clarification, including the regulation of the capture, farming and use of cleanerfish.

«We are currently shifting focus from detailed inspections of individual sites to following up the farms at company level. This way, we wish to make it clearer that we hold company management responsible for the safe and proper running of all company sites, and for taking effective measures to ensure long term improvements where necessary.»

«The authorities, including the Food Safety Authoritiy, the Ministry and other government bodies, must set out regulations and clarifications of the regulations which more clearly establishes the limits of acceptable fish welfare, and which at the same time is not a hindrance to the development we seek», writes Næsset. He stresses that it is «the responsibility of the industry itself that fish be kept and treated in accordance with the rights accorded by the Animal Welfare Act».

Researcher Annichen Kongsvik Sæteren characterises the Food Safety Authority’s response as a repudiation of its responsibility.

«The responsibility for making improvements cannot be left to those who have financial interests in carrying on as before. The fish is in practice without rights until such time as the authorities communicate where the line is drawn.»

Disagree on Welfare Indicators

Head of health and environment at the trade association Norwegian Seafood Federation, Henrik Stenwig, says to Aftenposten Innsikt that mortality and welfare is a major challenge for the industry.

«Seafood producers view mortality at the levels we are currently seeing as a serious problem, as it reflects complex challenges in fish health. Furthermore, the waste contributes to the environmental footprint per kilo of produced fish, and also leads to financial loss», says Stenwig. Still, he does not believe mortality to be a good welfare indicator. «That a fish is dead, says very little about how it was when it was alive.»

«Challenges in relation to welfare, disease and death are complicated enough in themselves, and become almost unmanageable if they are not viewed as separate areas for action», says Stenwig. He believes that there is change for the better, but admits that welfare in the treatment of salmon lice is challenging, especially in areas with high infestation levels where repeated treatments are needed.

Stenwig refers to the industry’s own experiences, which show that producers have succeeded in reducing the negative welfare consequences of delousing, and that their fish health personnel are reporting increasing numbers of successful delousing treatments. «The lice are sufficiently decimated, and the handling of the fish has been safe from a welfare point of view», Stenwig argues.

The trade association is one of the organisations which have given feed-back on the proposed White Paper on animal welfare, setting out proposals for how welfare of live fish can be quantified.

A Possible Solution

Professor Poppe believes that higher fish welfare can be achieved by a move away from fish farming in open pens.

«There are already many kinds of sea pens which are closed or semi-closed [where there are walls, but no floor]. In principle, a physical barrier is created in the uppermost layer of the water», he says.

The salmon louse lives in the upper layers of the water. By wholly or partly closing the pen and pumping water to it from the deep, the louse can be kept out.

This way, harmful delousing treatments may become a practice of the past. A closed sea plant will also reduce the risk of other diseases, algae and viruses getting into the pen.

A number of companies are in the process of developing closed, sea based fish farms. One research paper, commissioned by the seafarming network Stiim, estimates that investments in such facilities will increase from 10 to as much as 70bn NOK in the next 25 years. One company, which is already part of this new move, is Aquafarm Equipment. Based in Haugesund, on Norway’s south-west coast, they have adopted the ambitious motto: «Let’s change fish farming forever». They have cooperated with other companies and research institutes, like Marintek, DNV GL, Norconsult, Multiconsult and Sintef to develope their new pens which, after extensive testing and development, are now in production.

In Brønnøysund, by the Arctic Circle, Akvafuture has been producing salmon in closed sea pens since 2011. According to its CEO, Thomas Myrholt, they have no salmon lice in their 30 closed sea pens, simply because they use water pumped from a depth of 25 metres.

«When we tried to use water from 15 metres down, we got one louse into the pens», he says.

Akvafuture’s mortality rate is just under 5 percent, says Myrholt, and the weight of the slaughtered fish is between 500 and 700 grammes, while the average for the industry is over 2,000 grammes. «In practice, this means that they have 10 times more wastage than we have», claims Myrholt.

In his view, the cost of the electricity used to pump the water from the deep is marginal, if any, when compared to the use of electricity in the whole production cycle in open pens.

Technologically neutral? The Norwegian coastline is home to 4000 open pens. To replace them all with closed pens would require enormous investments. As a result, many ask if closed pens will ever be more than shopfronts for green initiatives, so long as they have to compete for the same production licences as open pen plants. Land based plants do not have to pay for their licences (but the issuing of licences is currently on hold). The Norwegian government still maintain that they are technology neutral. The photo shows the Haugesund-based company Aquafarm Equipment’s closed pen concept. Photo: Aquafarm Equipment

Even if the Norwegian government has the expressed aim of an emission free salmon farming industry, there is no framework to help such companies become profitable. Research, development and innovation is costly, also when the costs of salmon lice have been discounted.

The industry itself believes in growth and profitability for closed net pens at sea, if they are helped by the authorities in the form of special licences. While land based plants are exempt from the licence fee, closed sea plants are left to compete on the same, high cost terms, as open plants.

Thomas Myrholt of Akvafuture says the Solberg’s government [the previous conservative government, 2013-2021] pledged special licences to farms which were able to document that they, amongst other things, were free of lice and able to collect a certain amount of waste sediment (faeces and feed).

«But the decision was postponed several times. Now, we hope that the report from the governmental appointed Aquaculture Committee (AC), which is due this autumn, will deal with this issue.»

Vague Promises

«If you look at where the market is going, with EU taxonomy and documentation requirements, I believe closed fish farming will force its way in of its own accord.»

This statement was made by the then Minister for Seafood, the conservative Odd Emil Ingebrigtsen in spring 2021.

He wanted to «set a new course» for aquaculture at sea and announced that there would be a new initiative to stimulate «the sluicing of more of the current fjord based fish farming into closed pens».

The initiative never materialised. When the Solberg government announced its new strategy for marine aquaculture soon after, it did not set out any requirements for closed pens.

Open pens have been banned in Denmark, in southern Argentina and in four US west coast states, as a step to stop emissions and protect the wild salmon from diseases and genetic contamination from escaped farmed salmon. Canada is likely to ban open pens on its west coast by 2025.

In Sweden, a ruling by the Swedish environmental court put a stop to fish farming in open pens as early as 2017, a consequence of an EU ruling and new environmental quality standards for Swedish waters.

Trygve Poppe’s view is that Norway would do well to look into a similar ban, for diseases and fish welfare reasons, but also to capture harmful emissions of fish feces and fodder spill. As an alternative, he would look to incentivising the production, or production increases at farms with low mortality.

The Norwegian Veterinary Association has also long been of the view that mortality and fish welfare should be included as relevant considerations when licences to increase production is granted, not just the level of salmon louse infestation.

«The Veterinary Association expects that the Minister of Fisheries and Ocean Policy […], to start a process to turn around and change the expansion criteria, so we can get fish to our dinner table without too many bodies on way», said President Bente Akselsen of the Veterinary Association after the publishing of the Fish Health Report 2022.

A Huge Advantage

Henrik Stenwig in the Seafood Federation does not believe there is one single type of farming which can eliminate all health and welfare, problems, not even closed pens at sea.

«The challenges vary, and some measures are more effective with regards to salmon lice, which is just one of the problems. In addition, the financial costs differ, and the producers consider what is optimal for them, taking all the different factors into account.»

He believes open pens to be hugely advantageous to the industry, with water being replaced naturally and the energy savings this entails.

Drastic Measures Around the world, fish farmers meet more opposition than they do in Norway. Members of Ocean Rebellion protesting against salmon farming on 7 October 2022, outside the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh. Most of the world’s salmon farming takes place in Norway, Chile, Scotland, The Faroes, Ireland, Canada, The US, Tasmania and New Zealand. Photo: Russell Cheyne, Reuters/NTB

Points to New White Paper

The Minister of Fisheries and Ocean Policy [at the time this article was written], Bjørn Skjæran, does not believe a ban on open pens or making closed pens mandatory is the way forward. In an email to Aftenposten Innsikt, he writes that «Animal welfare should be high, regardless of which type of production the fish farmer choses to use. I cannot exclude that closed pens may be a solution to some environmental challenges in less exposed parts of the coast, where the power or waves, wind and current is not as great as it is in the outer parts of the coast.»

On the question of measures to improve fish health and welfare, the Minister points to the new White Paper on animal welfare, due in 2024, but also to the continuation of the governmental appointed Aquaculture Committee (AC), which are due to give their report this autumn – into how the licensing system can meet the current and future challenges. Their mandate has also been widened to look at technological developments which may promote further sustainable growth, according to the minister.

«There has been immense growth in marine aquaculture, which I am pleased about. At the same time, this growth has brought to the fore various biological challenges and the need for greater biosafety. That is why the AC is now also looking at how the concern for biosafety can become a part of the licensing system», writes the minister.

He also points out that the Government has incorporated the EU’s animal health regulations into Norwegian law, and that these regulations are also, to a large extent, concerned with preventing the spread of infections and infestations.

The Minister emphasised that for possible requirements for good fish health and welfare to work, it is necessary that the fish farmers themselves take on this responsibility.

Professor Trygve Poppe finds the attitude of the Ministry passive.

«The industry and the politicians have said similar things over many years. They acknowledge that the situation is not good, and they will work to improve it. But the problems persist, and show that new thoughts are needed», he says.

«It is time to take stock.»

Translated from Norwegian by: Hilde Syversen. Sources: Norwegian Veterinary Institute, Norwegian Food Safety Authority, Norwegian Institute of Marine Research, Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries, Regjeringen.no, Teknisk Ukeblad, E24, «Den nye fisken» by Kjetil Østli og Simen Sætre (Spartacus, 2021), Dagens Næringsliv, Akvafuture, Norwegian Veterinary Association, Norwegian Seafood Federation, Sintef, iLaks, Menon Economics, Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, Aftenposten, Norwegian Animal Protection Alliance, Reuters